Regarding their authors and the value of these writings, we refer to the authoritative judgment of Mons. Juan Antonio Presas in his work, Our Lady of Lujan. Critical-Historical Study 1630-1730, published as the third volume in this collection[1]. Here we will say only a few introductory remarks about each volume and present the methodology that we have followed in this publication.

Click on the image to see sample pages of the book

1. The Brief and Concise Chronicle by Fray Pedro Nolasco de Santa María

The first work is the account of the year 1737 that collects the testimony of a Mercedarian priest, Fray Pedro Nolasco de Santa María, presented before an ecclesiastical tribunal expressly formed to give consistency to the events of Lujan which up until that moment had been known only by oral tradition.

This chronicle has a fundamental importance in the history of Lujan, since upon it the other authors who have investigated and written concerning the origin, first miracles, and the primitive cult of Our Lady of Lujan rely.

The ecclesiastic tribunal before which Fray Pedro Nolasco de Santa María testified, had been established as a result of the canonical visit that Dr. Francisco de los Ríos, magisterial canon of the Holy Cathedral Church of Buenos Aires, made to the sanctuary of Lujan in January 1737, by commission of the Ecclesiastical Council of that episcopal see, at that time vacant. This was a memorable visit for Lujan, since the decisions and corresponding edicts made were to be very important for the future of the sanctuary. But the most important was the decision to create an ecclesiastical court in order to learn the origins, devotion, and cult to Our Lady of Lujan. Thanks to this decision we have today a first-rate testimony of those origins: precisely the chronicle of Fray Pedro Nolasco de Santa María.

According to the above-mentioned visitor, the decision to create the court was motivated by the fact that, “In view of so many wonders worked by the mediation of Our Lady of Lujan, it was impossible for him not to regret the total lack of individual and written testimonies of so many prodigies of great interest for the glory of God and his divine Mother, and desirous of remedying, as far as possible, the absence of such important manifestations of the power and goodness of the compassionate Protector of the inhabitants of these vast districts, he ordered to be drawn up, without loss of time, the act in the form of law, on the origin of the Holy Image of Lujan, the beginnings of this sanctuary, and the devotion that began with all the wonders, miracles and prodigies, that it may be known, either by tradition, sight, or other trustworthy channels, what God Our Lord has worked through such a Holy Image”[2].

The tribunal was presided by Fray Nicolas Gutiérrez, Franciscan, general preacher of his order and guardian of the convent in Buenos Aires, and was assisted by the public and ecclesiastical notary, Don Antonio de Félix Saravia. He was mandated to find out “with exact information from truthful persons of good reputation and opinion, and principally of those of greater years, who for the following purposes one may call upon and arrange to meet: to obtain knowledge of the origin of the mentioned Image, to whom it belonged, the beginnings of this sanctuary and devotion to the Image, with all the prodigies, miracles, and wonders that God has worked through this Holy Image until the present moment, by tradition, sight, or other means have heard or knew of”[3].

The interrogations took place first in Lujan and then in the ecclesiastical court of the Cathedral of Buenos Aires. “A great number of highly trustworthy people, of the best reputation and opinion […], attended, from all of whom [the judge] after the customary oath-the priests placing their right hands on their chests and swearing in verbo Sacerdotis, the soldiers on the cross of their sword, and the others on the book of the Holy Gospels or on the base of a Santo Cristo-took very detailed statements of how much they knew about the origin of the Holy Image of Lujan, in whose possession it was first, the wonders that accompanied its marvelous stay in the countryside of the River of Lujan, the beginnings of the sanctuary, the great devotion and extraordinary cult that the whole neighborhood and even the most remote regions began to practice toward the Sacred Image, and finally all the prodigies, miracles, and wonders that to date, by their own sight or by authentic tradition, are known as worked through the mediation of Our Lady of Lujan ”[4].

Father Salvaire reports that the volume containing all these testimonies was taken from the sanctuary in 1812 and lost[5]. However, some pages were preserved and are kept in the archives of the Basilica of Lujan. Fortunately, we have the entire account of Santa María and the testimonies of various miracles worked through the intercession of Our Lady of Lujan and witnessed by various people. Immediately following his chronicle, Santa María himself testifies to six miracles. The statements of other witnesses then follow[6].

It was before that court and with this solemnity that, under oath, Fray Pedro Nolasco de Santa María, who enjoyed a good reputation, was declared a “person of authority and teacher in his Order”, as the conclusion of the statement says.

Pedro Arruz y Aguilera, as Fray Pedro de Santa María was called before his entrance into the Mercedarians, was born in Buenos Aires in 1666, son of Spanish parents. He entered the order very young, and from early on he was given positions of responsibility. He was a teacher, and served as head and procurator of the Mercedarian convent in Buenos Aires. As such, he was a person of recognized authority. On two occasions he was provisory chaplain of the chapel of Lujan, and personally met almost all of the persons mentioned in his chronicle, among whom were Negro Manuel, Dona Ana de Matos, and the first chaplain, Fr. Pedro Montalbo. He died between 1746 and 1753.

His chronicle is the most ancient writing of historical character which is preserved concerning the primitive events of Lujan. The testimony is brief and concise. But it is of unique valor in witnessing to the truthfulness of the origins of Lujan, because it recounts events narrated by contemporary witnesses to the miracle (his father and great grandmother) which the author himself had heard; also because he met in person the principle protagonists of the first history of Lujan, and finally due to the authority which Santa María himself enjoyed and by the circumstance of a statement made under oath and before a formal ecclesiastical court that had instructions to act “with all exactness” in questioning “truthful people, of good reputation and opinion” .

In relation to the manuscript conserved in the archives of the Basilica of Lujan, Mons. Presas recounts that Fr. Salvaire, in the notes which are conserved in the same archive, affirms that the secretary who wrote down his testimonial account was Dr. José de Andújar, the first pastor of Lujan: this is deduced by the strokes of the letters and the handwriting[7].

The part of the manuscript which has been preserved begins with the chronicle of Fray Pedro Nolasco de Santa María, which takes up nearly two pages, and which is followed by a series of miracles worked by Our Lady of Lujan, as asserted by diverse witnesses. The first of these miracles, related by Santa María himself, is recounted towards the end of the second page.

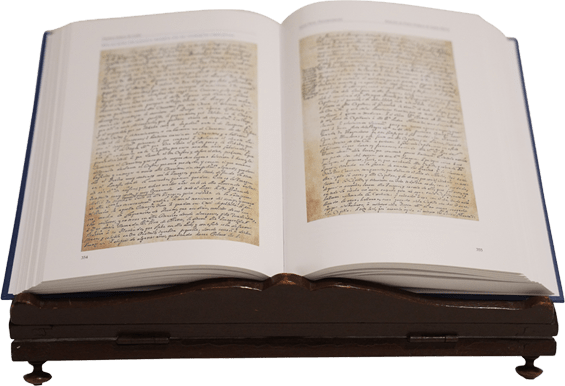

Due to the unique importance of this document, we have published the photographs of these first two pages of the manuscript[8]. In the transcription of the text, which we present below, we have modernized the spelling, also indicating the meaning of some of the words which today are no longer used, and we have divided the writing into paragraphs according to the story line which Santa María will mention in his account.

2. The True History by Fathers Oliver and Maqueda

The second work is a history even more extensive and detailed then former, written by Fr. Felipe José Maqueda in 1812. The text is completed by a Novena to the Virgin of Lujan, and the ancient Joys of Our Lady.

Fray Antonio Oliver was born in Palma de Mallorca in 1711[9]. When he was 16 years old, he was invested in the habit of the Franciscan Order. While still very young, he excelled in the study of philosophy and theology and was named master in both disciplines. He was a very cultured man, dedicated to study and knew the ancient languages (Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic), proficient in grammar, translator of the classic Latin authors, author of works in moral and spiritual theology and the chronicler of his Order.

While suffering from a grave sickness, he made a vow to offer himself for the missions if he recovered his health, and was miraculously cured. He obtained the title of apostolic missionary, desiring to spend the rest of his life dedicated to work for the conversion of the pagans. He therefore left for Peru in the year 1751 and his first mission was the celebrated missionary convent of Santa Rosa of Ocopa. In 1755 he arrived to Tarija, with the mission to rebuild the convent which would later become the Collage of the Propaganda Fide. Fray Antonio was named Guardian in two distinct periods.

Around the year 1770, he arrived to his last mission in Buenos Aires, where he would live until his death, which took place on May 31st, 1787. In Buenos Aires, Fray Antonio wrote numerous books on religion, theology and spirituality, but most of his works were never published. He was the inspector of the third order and chaplain of the convent of the Capuchin Sisters of Our Lady of Pilar, for whom he composed varies writings, among which is found the Mystical Catechism for the Instruction of Religious and a Commentary of the Rule of St. Claire. During his years in Buenos Aires his reputation as a wise and holy man grew. He was a man enamored of the Virgin of Lujan, for whom he became historian.

We do not know the exact date on which he composed his History, but it was probably around 1780.

This work would have suffered the same fate as the majority of his writings if the manuscript had not been collected by the priest, Felipe José Maqueda, assistant pastor of Lujan, who had it published in Buenos Aires in the year 1812, adding texts of his own. It is, without a doubt, Father Maqueda’s poetry with which the work opens, as it bears his signature and also contains some autobiographical references. In the opinion of Mons. Presas, Maqueda would also have completed Oliver’s story based on the account of the confirmation of the chaplaincy of Pedro Montalbo by Bishop Antonio de Azcona Imberto[10].

Father Felipe José Maqueda was born in Buenos Aires on August 22, 1740. On his mother’s side, he was the nephew of Dr. Carlos José Vejarano, pastor of Lujan since 1770. He was the fourth of five children, three of whom became priests. The second, Andres, became a Dominican friar while Felipe José and his younger brother, Gabriel José, became diocesan priests. Both spent their entire priestly lives in Lujan: Felipe José as assistant to his uncle in the parish, and Gabriel José carrying out his duties as chaplain of the sanctuary of Our Lady.

Fr. Felipe José Maqueda died September 20, 1815 after have published the History with the attached Novena in 1812.

Some copies of this first typographic edition from 1812 have survived in good condition even to this day[11]. That which we have reproduced here in photographic copy is conserved in the Historical Museum of Lujan Enrique Udaondo.

The original size of the typographic text is quite small, measuring 88 millimeters wide by 133 millimeters long. To make it easier to read, we have published it slightly enlarged.

Although the typographic text is well preserved and is perfectly legible, we have found it useful to offer next to the photograph of each page the transcribed text according to the current use of the Spanish language, correcting in some cases the spelling and punctuation, and indicating in a footnote where it was needed, the meaning of words no longer used today.

When the author writes in the form of poetry, we have not modernized the text so as not to lose the beauty of the writing. That is why the reader will find some expressions that may be old fashioned but that do not represent any difficulty for understanding.

As for the proper names and last names that are presented using different spellings throughout the work, we have chosen to unify the way of writing them according to the spelling used most frequently in other ancient documents where the same names are mentioned.

It should be noted that the author uses once in the History and 10 times in the Novena the verb “to adore” referring to the Image of Our Lady of Lujan (pg. 10, 39, 43, 48-two times-, 51, 54, 58, 59, 63 of the original edition). Evidently this does not refer to the act of adoration which implies the cult of latria, which is due to God alone, but the verb should rather be understood in the sense, “to love with extreme”, “to place in a person or thing one’s esteem or veneration”, “to venerate”, meanings which are all found in the Dictionary of the Spanish Language[12]. In sacred images, in fact, we venerate that which they represent, as Catholic doctrine clearly points out[13], and it is in this sense one should understand the author’s statements[14].

3. Legend and History of the Virgin of Lujan by Dr. Raúl A. Molina

The third work is a study by Dr. Raúl Alejandro Molina (1897-1973), honorable member of degree of the National Academy of History of Argentina, titled Legend and History of the Virgin of Lujan, published in the Bulletin of the National Academy of History, Year XL, Buenos Aires 1967, pg. 151-197. It is a keynote lecture with a long historical and documentary appendix[15].

Molina himself defines and explains the valor of his exposition: “To the history of Lujan, rooted for more than three centuries, I must add today some information, that, if it will not modify that miracle, as divine as it is simple, it will surround it with the historical framework which it lacks”. His study, solidly based on the documentation which the author found in the archives he had consulted, was a very important milestone in the history of Lujan and deserves to be placed among the foundations of Lujan historiography[16].

In fact, Molina’s work was decisive in determining the place where the miracle of Lujan occurred, when in his research he found the documentation referring to the location of Rosendo’s ranch. It was also decisive in order to confirm the historical existence of the persons who appear in the ancient chronicles, hence giving documental consistency to the primitive events of Lujan.

On the other hand, his conclusions concerning the date of the miracle have been superseded thanks to the subsequent discovery of other documents.

Molina, in fact, based mainly on the young age of one of the characters mentioned in the ancient chronicles, Diego de Rosendo, dates the miracle in 1648, that is, at a later date than that stated in Oliver-Maqueda’s chronicle (the year 1630), and which was traditionally accepted.

For Molina, the fact that in 1630 Diego Rosendo was twelve years old is decisive; hence he would not have been able to carry out the responsibilities of ownership of the ranch. He concludes, therefore, that the miracle took place various years later. However, later studies have exceeded this apparent difficulty, confirming the traditional date of 1630[17]. But it is noteworthy that these later discoveries were due, at least in part, to the incentive that Molina’s hypothesis aroused by questioning the date that tradition and the Oliver-Maqueda history set for the miracle.

This divergence in the date of the miracle does not detract from Molina’s precious study, quite the contrary. It is enough to read the praise that the most accredited Lujan scholar, Mons. Juan Antonio Presas, makes of this work and its author, when he presents him as one of the great historians of Lujan:

“With his work, Molina does not try to destroy anything that the previous historians have said, but rather to put things in their place according to the modern procedures of science; he does not correct the traditional legend, but rather provides it with the historical aspect that, until then, it lacked. Santa María gave us the first, fresh and simple account of the miracle; Maqueda put together in a booklet, without much examination, all the tradition, legend and commentary he heard on the subject; Salvaire, with his prestige, aroused the attention of the people to the miracle of Lujan. However, his narration lacked the criticism and analysis that the world of progress demands today; for this reason, Molina completes the work by presenting it to the public with the demands which modern investigation requires […] The work of Dr. Molina […] was like a stone cast into a calm lake which broadened the circles of scientific research. His lecture broke new ground in the field of Argentine Marian history, and it is the greatest monument that faith and science have erected in recent times to the Sovereign Lady of the Pure and Immaculate Conception of the Lujan River.[18]”

Regarding the methodology used in this edition, the following should be taken into account:

-The text of Dr. Molina’s lecture is presented in its entirety, even though we omit the accounts of Fray Pedro Nolasco de Santa María and that of Felipe Maqueda, which the author places at the beginning of the Documental Appendix, since they are already published in this same volume. We indicate the omission with an asterisk.

-The published text in the Bulletin of the National Academy of History contains several editing errors. They are probably due to the fact that it treats of an oral lecture, given in one of the sessions of the mentioned Academy and which was later published without the rigorous editorial care that such a study would have required.

In this edition, we have corrected the most notable editing errors, for example, the confusion of some of the names of the main protagonists, indicating the corrections in a footnote. In some cases, it has been necessary to improve the wording to facilitate understanding, with additions that we place between brackets.

-We have respected the spelling used by Molina in the writing of the ancient documents. For this reason, the reader will find obvious writing errors that do not, however, make it difficult to understand the texts.

– We have unified the spelling of some names of the personages that in ancient documents, as is common in these cases, appear as written differently.

-We have preferred to place in footnotes the references to the cited documents as well as the archives where they may be found, which in the original were placed between parenthesis in the very body of the text, which made reading somewhat difficult. In addition, we have specified the acronyms and abbreviations that Molina uses to cite these documents and archives.

We have also included, as an introduction to the text, the words with which Dr. Miguel Ángel Cárcano, then President of the National Academy of History, introduced Dr. Molina’s prolusion and which were published in the same Bulletin of the National Academy of History.

The Editors

[1] In Part One: Writers, pp. 51-58 (Pedro Nolasco de Santa María); 59- 66 (Antonio Oliver and Felipe José Maqueda); 81-87 (Raúl Alejandro Molina).

[2] J. M. SALVAIRE, History of Our Lady of Lujan, ch. 20, III; in this collection, volume 2, volume 1, p. 475.

[3] Order of commission of Fray Nicolás Gutiérrez to preside over the mentioned tribunal, in J.M. SALVAIRE, History of Our Lady of Lujan, chap. 20, III; in this collection, volume 2, book 1, pg. 476. The final commission of the visit, which includes such a disposition, in Appendix D, XXIV of the same work; in this collection, volume 2, volume 2, pp. 570 ff.

[4] J. M. SALVAIRE, History of Our Lady of Lujan, ch. 20, IV; in this collection, volume 2, volume 1, p. 477.

[5] Ibidem, ch. 20, VI; in this collection, volume 2, volume 1, p. 478.

[6] The series of miracles attested by various witnesses and contained in the manuscript can be found in J. M. SALVAIRE, History of Our Lady of Lujan, ch. 20, IX-XXI; in this collection, volume 2, book 1, pp. 481-490. Also transcribed in his extensive collection of documents is J. A. PRESAS, Our Lady of Lujan. Critical-Historical Study 1630-1730, Sixth Part: Documentation, First Documents, year 1737; in this collection, volume 3, pp. 512-521.

[7] Our Lady of Lujan. Critical-historical study 1630-1730, Part One: Writers, Pedro Nolasco de Santa María; in this collection, volume 3, p. 57.

[8] We have taken them from J. A. PRESAS, Our Lady of Lujan. Critical-Historical Study 1630-1730, Buenos Aires 1980, pp. 228-229 (in this collection, volume 3, pp. 354-355).

[9] We take the biographical information about Fray Antonio Oliver from M. A. POLI, “The Virgin of Lujan and her Franciscan chronicler, Fray Antonio Oliver Feliu, O.F.M (Palma de Mallorca 1711-Buenos Aires 1787)”, New World 8 (2007) pp. 81-106. also published in Bulletin of the Lul.liana: Archaeological Society: Journal of Historical Studies 64 (2008) pp. 289-308.

[10] Cf. J. A. PRESAS, Our Lady of Lujan. Critical-Historical Study 1630-1730, Part One: Writers; in this collection, volume 3, p. 66.

[11] Of this True History of Oliver-Maqueda there were other editions in century XIX: one of 1837, published by the Argentine Press (Buenos Aires); another in 1852; another in 1864, published by the Printing Press of Mayo (Buenos Aires); another in 1876 published by the Fathers of the Congregation of the Mission; another in 1887, published in the La Voz de la Iglesia Press (Buenos Aires). There were also several editions in the twentieth century; see M. A. POLI, “The Virgin of Lujan and her Franciscan chronicler Fray Antonio Oliver Feliu o.f.m. (Palma de Mallorca 1711-Buenos Aires 1787)”, in Bulletin of the Lul.liana Archaeological Society: Journal of Historical Studies 64 (2008) p. 306.

[12] Royal Spanish Academy, 23rd Edition, Madrid 2004, voice “Adorar”

[13] See Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2131-2132; COUNCIL OF TRENT, XXV Session (December 3-4, 1563): Denzinger-Schonmetzer 1821-1825; COUNCIL OF NICEA, 7th Session (October 13, 787): Denzinger-Schonmetzer 600-601. For the theological reason for this veneration see also St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II-II, 81, 3, ad 3.

[14] It is noteworthy that Father Salvaire, while refuting the opinion of those who think that Catholics worship images in themselves, nevertheless uses “to adore” in this other sense; History of Our Lady of Lujan, ch. 17, V-XII; see ch. 6, XI; ch. 9, I; ch. 34, X; ch. 44, XV; Appendix S; Appendix Yb. Some of these texts are quotations from other authors.

[15] The document was kindly sent to us in photographic copy by Mrs. Mariana Miriam Lagar, Director of the Library of the National Academy of History.

[16] In the words of Cardinal Mario Aurelio Poli, Archbishop of Buenos Aires, this study “marked a before and after in the investigation of the Miracle of Lujan”; Letter to Fr. Gustavo Nieto, Superior General of the Institute of the Incarnate Word, March 9, 2019, p. 2.

[17] On this point see J. A. PRESAS, Our Lady of Lujan. Critical-Historical Study 1630-1730, Second Part: Bases, The date of the miracle, volume 3 of this collection, pp. 133-135. Bishop Presas concludes: “When the said scholar read his lecture, it was difficult to give a full solution to the difficulty, since many of the documents that we have presented throughout our dissertation had not yet been discovered or were not yet known. But, thank God, this difficulty has spurred us to go deeper into the date, and we have gained by duly interpreting the documents, and weighing with greater accuracy the various parts of the Lujan account”; p. 133, footnote.

[18] Ibidem, Part One: Writers; in this collection, volume 3, pp. 86-87.