Its author was born in Castres (France) in 1847 and was ordained a priest in Paris in 1871. During the same year he arrived in Argentina as a missionary and visited for the first time the sanctuary of Lujan (which had been built by Lezica and Torrrezuri), remaining captivated by the Image of Our Lady. He was a great missionary, and in two distinct periods he missioned in the lands of the Indians. During one of these occasions in the year 1875, he was miraculously saved from a sure death by the hands of the Indians through the intercession of Our Lady of Lujan. Dedicated completely to the diffusion of the devotion to Our Lady of Lujan, he undertook the writing of her story and traveled to Rome in order to obtain from Pope Leo XIII the pontifical coronation of the Holy Image (which occurred through the hands of the archbishop of Buenos Aires, Mons. Aneiros on May 8, 1887), for which he had chiseled in Paris a rich crown that was blessed by the pope. He magnanimously planned and began the construction of the current extraordinary church, whose cornerstone was blessed on May 15, 1887.

Click on the image to see sample pages of the book

Click on the image to see sample pages of the book

Apart from the History of Our Lady of Lujan, Fr. Salvaire wrote other works for the devotees and pilgrims and founded La Perla del Plata, the magazine of the sanctuary. Animated by great apostolic zeal, he carried out great pastoral work in Lujan as chaplain and rector of the sanctuary. He founded the Hospital of Our Lady of Lujan, the Circle of Catholic Workers, the School of Our Lady of Lujan, the Pilgrim’s Rest, the Conference of Ladies of St. Vincent, creating numerous parochial associations. He died on February 4, 1899 at only 52. He is buried in the right transept of the Lujan Basilica. His cause for canonization is ongoing[1].

Regarding the motivation of his work, when Fr. Salvaire was miraculously saved from death through the intercession of the Our Lady, he made a vow to spread and make known the devotion to the Immaculate of Lujan. He himself says the same in the dedication of his colossal work: “My sweet Mother, I myself have experienced in an unspeakable way the wonderful influences of your tender protection, of your power and boundless goodness. Let this right hand remain still and without movement, stop my tongue, if ever during my life my heart comes to forget your marvelous intervention on my behalf and the promise that I made to you so urgently, to consecrate all my faculties to make you known as you deserve, to spare no means to praise you and commend your power and maternal tenderness, and to spread, as far as possible, to the furthest reaches of this Republic, your beautiful and sweet legend. This book, kind Protector, is the fulfillment of my unforgettable promise”[2].

Salvaire set out to base his story on historical documents, for which end he had to work diligently, investigating “in all the archives of the colonial period”, as he himself relates: “Thus disposed, I eagerly dedicated myself to the study of everything that could be related to the history of the sanctuary and of the Villa of Our Lady of Lujan, as I have already said, all the archives of the colonial era, because I was fully convinced that if, as Carlos XII said, history should be a witness and not a flatterer, only in the original documents deposited in the archives would one discover, together with the truth, that color that reveals an era and manifests an age, better still than the most perfect narration or description”[3].

The valor of this praiseworthy history, with whose composition Fr. Salvaire was intensely occupied during eight years, is truly singular. Later scholars have shown that from a critical-historical point of view, it has certain limits, particularly with regard to the first period of Lujan’s history, however they do so while still highly valuing his work. However, these limits, due to the historical circumstances in which Fr. Salvaire worked, in no way diminish the valor of his writing, which laid many of the foundations for the work of successive historians.

The great historian of Lujan, Mons. Presas, affirms that the History of Salvaire was “unanimously” applauded by critics of the time. And after citing numerous praiseworthy testimonies of that time, he concludes:

“We fully endorse and reaffirm these judgments, which even today critics respect in their entirety. However, we make a few observations about the History. It covers a period from 1630 to 1885, the date of its printing. And even though the work still retains the gravity of a well-documented book today, not all its parts carry the same weight or enjoy the same authority.

Thus, the first chapters dealing with the origin and cult of Our Lady of Luján, because Fr. Salvaire was lacking the primary contemporary documentation concerning the events, they lack that experience that gives the story the stamp of authenticity. Its most valuable part is that which runs from the years 1730 to 1815, since for the work he had a whole storehouse of first-hand documentation in the same sanctuary and in the Municipality of Luján. The part that is from the year 1815 until its publication is astonishing by the amount of data that refers to favors and graces of the Virgin of Lujan, as well as of acts of honor carried out by those who gave ex-votos; but because the author lacks the perspective of time, many other events of that time have been forgotten, as they have not been recorded.

Today we know much more about Our Lady of Lujan then the religious Salvaire did, since time does not run in vain. But this science and knowledge that we currently have of the events of Lujan are the fruit and thanks to the concern, study, commitment and zeal that animated the spirit of Salvaire. His work in that period was that of a giant: a colossal hymn of love and gratitude to the Mother of God; a trumpet call that resonated to the ends of the homeland and the world, in an effort to make known more each day this Virgin, Mother, and Queen of Lujan”[4].

From the methodological point of view, we have adopted the following criteria in this edition:

- The division into two books is the same as Fr. Salvaire’s original edition of 1885

- In the original edition, Fr. Salvaire divides the work’s content into three large parts, for which he uses different types of page numbering. Thus, the 44 chapters are preceded by an extensive introduction of various documents and followed by a long documentary appendix.

The outline is the following

I. The Introduction (in the first book, 131 pages numbered with roman numerals), which includes:

- The declaration of the author

- The dedication to the Virgin of Lujan

- Letters of ecclesiastical and civil authorities

- A study written by S. Estrada about the sanctuary of Lujan

- An introduction to the work, written by Fr. Goyena

- The prologue by Fr. Salvaire

II. The History of Our Lady of Lujan (with Arabic page numbering starting again in each book). It includes:

- Chapters 1 to 24 (first book, pages 1-458)

- Chapters 25 to 44 (second book, pages 1-496)

III. Appendix (the second book contains Arabic page numbering within parenthesis, pages 1-287)

In this edition, on the other hand, we have numbered all the pages with Arabic numbers in each of the two books of the work, including the introductory part and the appendices.

- We have corrected the text of Fr. Salvaire in his spelling and on some occasions, in his style, in order to facilitate reading. In no case has the meaning of the sentences been changed and its text is reproduced in its entirety.

- A particular problem represented is the spelling of the many documents cited in the work. Fr. Salvaire, who had the documents in front of him, affirms that in some cases he had to correct them[5]: “Certain documents of which appear in this book have undergone a few small modifications of style and particularly in spelling which in no way effect the meaning of the phrase, and which I have deemed necessary to insert in order to adjust the tone of the work to a more uniform and correct language. In a few of these documents, there were noted some very evident errors and that in correcting them it seemed to be a service which should not be denied to the letters, as long as great care is taken to respect the value of the words”.

We do not know what these corrections introduced by Fr. Salvaire were, since many of the cited documents were lost. Moreover, in the case of ancient documents, we have found it better to respect their original writing. For these reasons we have chosen to transcribe the citations of these documents as they were by Father Salvaire, without spelling corrections, even when the errors are evident. This applies mainly for those documents which Fr. Salvaire uses as his resources, and especially for the extensive collection of documentary appendices that he places at the end of the second book.

On other occasions, particularly when it comes to testimonies without reference to the source or citations from old books that we have been able to confirm, we have corrected spelling errors.

- We have improved the page numbering, completing and correcting the references of the cited works which were missing or contained errors. Moreover, we have omitted repetitions and have unified the type of font used to indicate the authors as well as the titles of the cited works, using the same criteria as in the other volumes of the collection. We have also unified the names of the different mentioned archives, since Fr. Salvaire sometimes uses distinct names in reference to the same archive.

- In relation to the citations of the Sacred Scriptures, we have corrected a few errors and have replaced the ancient names of the Sacred Books with those which are currently used (ex. I-II Paralipomenon, today is 1-2 Chronicles, etc.).

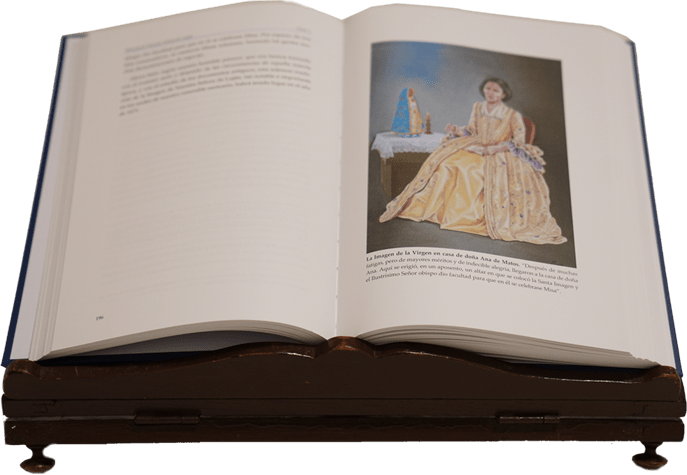

- We have illustrated the work with oil paintings by Sr. María de Jesús Sacramentado Riera, SSVM.

The Editors

[1] On Fr. Salvaire, see J.M. PRESAS, Our Lady of Lujan. Critical-Historical Study 1630-1730. First Part, Writers, volume 3 of this collection. Also by the same author Jorge María Salvaire. The Apostle of the Virgin of Luján, Morón 1990. Bishop Presas says that the best biography of Salvaire, up to that moment, is that of F. C. ECHEVARRÍA DE LOBATO MULLE, Father Salvaire and the Basilica of Luján, Luján 1959.

More recently, the monumental work of Mons. JUAN GUILLERMO DURÁN has been published in several volumes: Father Jorge María Salvaire and the Lazos Family of Villa Nueva. An episode of captives in Leubucó and Salinas Grandes. In the origins of the Basilica of Luján (1866-1875), Buenos Aires 1999; In the Shade of Catriel and Railel. Missionary work of Father Jorge María Salvaire in Azul and Bragado (1874-1876), Buenos Aires 2002; From the border to the Villa de Luján: the great Chaplain of the Virgin Jorge María Salvaire (1876-1889), Buenos Aires 2008; From the border to Villa de Luján. The beginnings of the great Basilica, Buenos Aires 2008; Jorge María Salvaire, C. M., Great Apostle of the Virgin of Luján, “Another Negro Manuel”, Buenos Aires 2016.

[2] History of Our Lady of Lujan, volume 1, pg.11. Also mentioned in the Prologue.

[3] Prologue, pg. 88.

[4] Our Lady of Lujan. Critical-Historical Study 1630-1730, First Part, Writers, third volume of this collection

[5] Prologue, pg. 96.